In product development, original idea takes lots of transformations on it’s way to the actual implementation (writing code which works and provides desired benefit, that is). One of those is transition from sketches/designs (“sketches” further) done by UX/designer into actual stories that developers would take to iteration.

Writing stories should not be a big deal after practicing for a while. Some of the information writing stories can be found in one of our previous blog posts, titled “User stories: why?”. This article is focused rather on process prefacing writing the stories and way to make sure stories would sustain and would add up into solid, consistent and deliverable chunk of the scope.

Previously, we mostly relied on design review process as a tool to make sure sketches are consistent and we can proceed with them. But, as it turned out, it’s quite difficult to keep all the product functionality in your head while reviewing the designs.

This is one of biggest challenges we faced on this path. In other words, sketches often don’t guarantee they consider all the possible flow twists, functionality dependencies and all the possible states application may get into. As the worst outcome, overlooking such things may result into the case when your team finds itself in the situation when stories are written (based on inconsistent sketches), estimated, prioritized and planned out, but when it comes to implementation, some states are missing, weren’t thought through and discussed.

As a result, stories get blocked by unclarity, and iteration scope becomes undeliverable pile of code waiting for clarification.

No need to say that collateral damage here would be overall team frustration because of inconsistent scope and unsuccessful design review, more time to be spent on back-and-forth communication in order to clarify etc.

And for the whole process the result would be broken product development cycle and postponed feature delivery…

In this article we wouldn’t dive deep into possible reasons of outcomes like this. Based on my experience, quite often it happens due to the fact that UX specialists and designers are focused on providing convenient and easy-to-use interface, maximizing conversions and making flow easily understandable rather than on building the interface from functional perspective. By “functional perspective” I mean owning the context of currently existing functionality, its technical features and functional dependencies.

Just to make it clear, that’s not any kind of blame or accusing. Everyone has own focus. And it’s totally not wise to demand owning of technology context from UX or a designer. That’s why a product manager and a lead engineer are listed in the line-up.

So let’s get to more positive :)

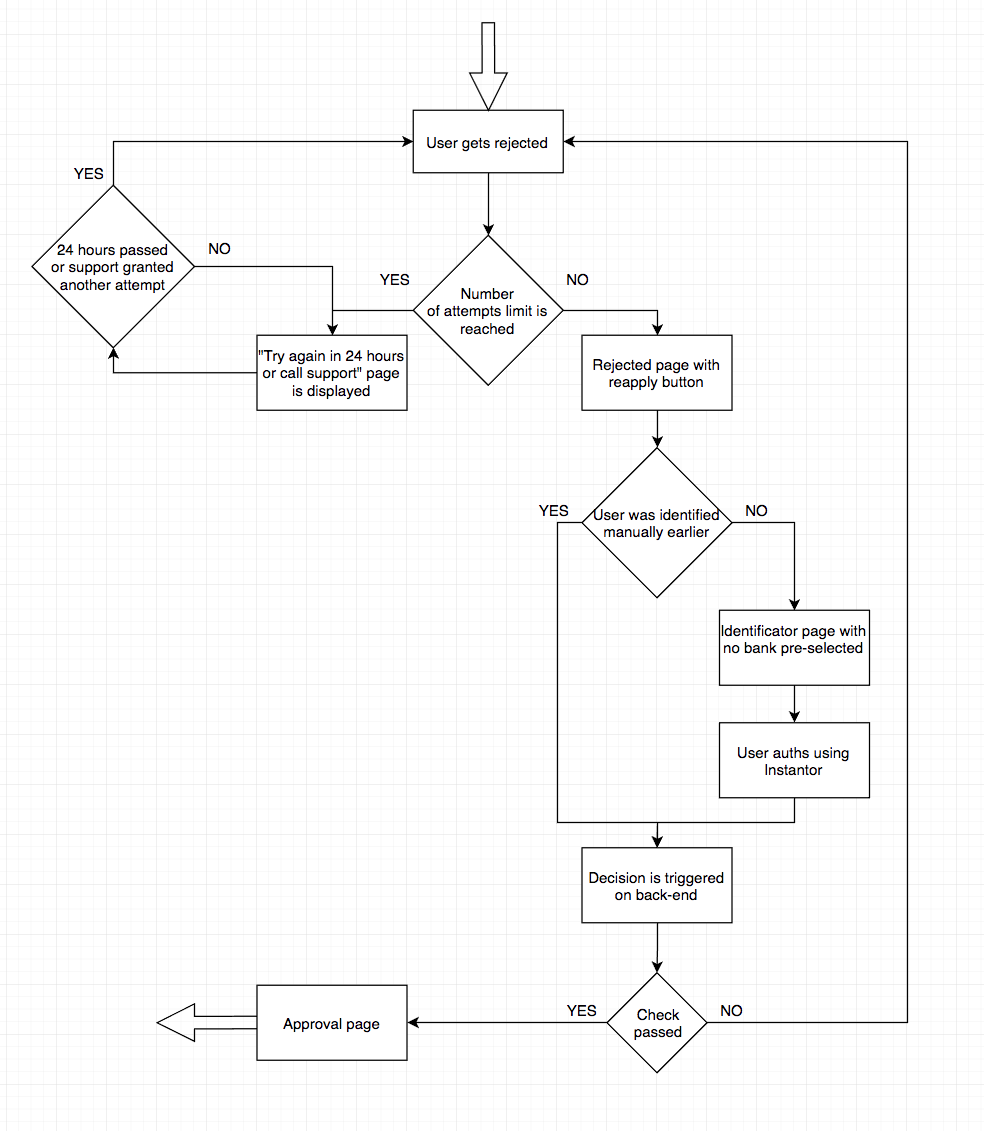

Solution that helped us minimize outcomes described was “flowcharts”. At first, this sounds nearly ridiculous but it turned out to be a good tool to use to organize scope and put it in schematic way.

In a nutshell, approach is very simple: before sketch work is started (or in the course of) product manager or lead engineer (any person who owns functional context of the application to the extend of understanding functional dependencies and possible states) sits in pair with an UX expert or a designer (or asynchronously) and produces logical schema of upcoming functionality using generally accepted figures.

Pros:

- organises feature flow logic

- clear and simple to use

- no special tools needed (you can use things like draw.io but even piece of paper and a pencil would do great)

- easy to explain even to a completely non-technical person

- easily readable by any team member even with no code possession

- prominent single source of truth about feature/flow

- adjustable to the wide set of options from top level steps to pretty much precise details

- each step can be extended with corresponding screen or made as link to Invision screen

- serves as an easy reference to create linked screen flow (e.g. using Invision or Axure)

Cons:

- requires some additional time to sync on comparing

- natural resistance for injecting anything new into the “established” process