Product is a soul living in a technical implementation

— Yaroslav Lazor

Under the hood of all software products we use on a daily basis, there are numerous lines of code that allow us to read the news, communicate with friends, watch videos, listen to favorite artists and perform other online/offline activities using electronic devices. For this reason, the quality, reliability and performance of the software directly depends on the code quality – the higher the better.

In this article, we’re going to talk about one of the most widespread code review concepts and share Railsware’s hands-on experience in that process. Code is as important as the value it creates.

What is a pull request?

The best way to explain a GitHub pull request is from a practical standpoint. For that reason, we attempted to address the most obvious questions like “How to submit a pull request?” or “Why do we need to make a new branch git?” and give domain-specific answers.

The initiation of a specific code review procedure within a GitHub repository underlies the pull request definition. In layman’s terms, a developer asks his fellow developers to check whether his/her code changes are applicable. Pull requests are usually leveraged by teams and companies that collaborate through the shared repository model, as well as numerous open-source projects on GitHub.

Though it may seem a rather simple and unremarkable procedure, in practice, it has particular pitfalls, as well as benefits, to consider. If this is a new topic for you, it’s highly advisable to check out the GitHub Glossary to familiarize yourself with some key terms we will use in the article.

Why are pull requests useful?

The usefulness of pull requests can be broken down into 3 major functions: keeping the team’s work separate as it gets bigger (to allow parallel development without interruptions and running into conflicts), sharing knowledge and increasing code quality and cohesion. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Work separation and conflict resolution

Railsware, being a product studio, uses an iterative approach to code. It means, our engineers make small evolutionary iterative changes underway. If the team gets bigger, it is crucial to keep engineers’ work separate to avoid conflicts. In general, the workflow is carried out through adding lines and removing lines. It is great in terms of resolving conflicts that happen in the same file but not if they happen in the same context.

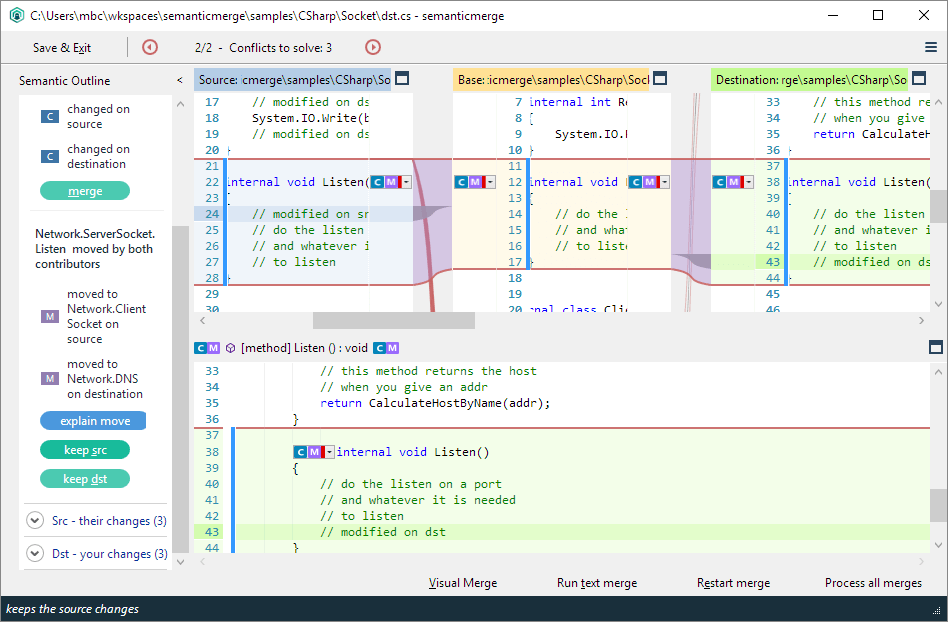

Let’s say there are two branches, and two engineers start working on the same codebase in the same place. They’ve introduced changes in the exact same place, which will cause a conflict. When you need to make big structural changes in the codebase like changing directory structure or coding conventions with the involvement of a number of engineers, be prepared for plenty of conflicts that have to be resolved manually. However, you can always opt for a merge tool as a solution to ease the conflict resolution process.

Usually, these tools work as follows: there are three columns, the left and right column display the conflicting changes and the middle column the result. Simply choose which change you want to accept, and the middle column will display the outcome of the conflict resolution.

Upgrading quality and cohesion of the code

People think in different ways. When coding something, you always think it is easy-to-understand because you built it. This is called author bias. However, someone might not get what you built or created, because he or she has a different perspective.

This need not be a bug or error. A reviewer might notice some inconsistency with the generally agreed upon concepts and practices, as well as a limited vocabulary in the team/company. For example, if we build a loyalty reward app, we might use the term “coupon” or “offer”, but instead of having them both in the code, we should pick one and use it consistently across the codebase and the product team. It’s very important to avoid ambiguous terms and choose one term over its synonyms.

We can also start using some similar approaches within a single project or codebase, and then extend it across many others. For instance, two separate teams use two codebases of one product for different mobile platforms (iOS and Android). That allows us to reuse some parts of the code or leverage common design patterns. Author and reviewer share equal responsibility for code quality.

Only this mindset guarantees thorough reviews and deep understanding of changes.

Knowledge sharing

Our attitude to peer review is not limited to the end product’s quality. In our striving to polish the code, we also level up our engineers’ expertise. The code review collaboration allows our engineers to enhance their domain knowledge and attain valuable experience.

We have lots of knowledge to share with you. Join Railsware team.

Flow of a pull request

The general Git pull request workflow consists of the following stages:

- Create a feature branch

- Make and commit changes

- Open a pull request

- Request a review

- Get reviewer’s comments

Your last step of dealing with the branch is actually to open a PR. While the branch creation procedure is straightforward (we need it to try out new changes without affecting the master branch), other stages deserve particular attention.

Commits

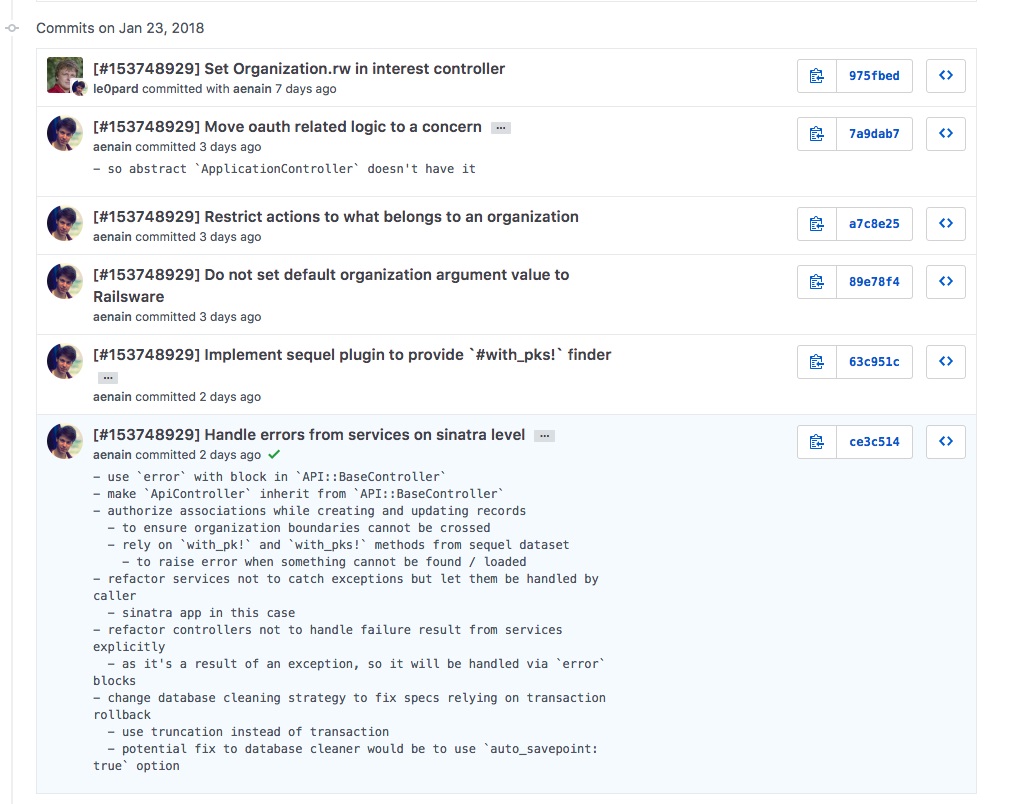

Commit is the name of a changeset you’re going to apply as a part of this branch or copy to another one. On that account, it is important to make them small and atomic (undividable). A title of the commit or a commit message is usually short (up to 100 characters).

Optionally, you can add an extended description/message. The commit message shall provide an explanation of reasons for changes answering the questions of what has been changed, in what way, and why. Thus, you do not even have to look at the code to see what happened.

The following context requirements are recommended to make your commit message as comprehensible as possible:

- Contextual details of the change reasoning

- Effects on other parts of the code (side-effects)

- Any domain knowledge involved in code-making

Connecting the branch name to the story ID is another interesting solution we use. The branch can be attached to the story tracker so we can see it. Whenever you create a commit, you can run some arbitrary code with git hooks. Railswarians use this to run the code, which prepends the commit message with story ID automatically based on what is in the branch name.

Commit messages act as just-in-time documentation, which helps developers understand the change during the GitHub pull request code review and in the future.

Attention: Comments in the code as an alternative to commit messages are less efficient because they can easily become outdated if a developer has changed the code but forgotten to update the comment.

Self-review

At Railsware, we value our colleagues’ time, so creating a pull request without a preliminary self-review is bad manners. Self-review involves checking the code for typos, errors, possible previous commits or changes from a fresh author’s perspective. The goal of this activity is take a detached view of the code and brush it up before creating a PR and asking other engineers for the review.

Requesting a review

It is important to emphasize that making a PR is not the same as requesting a review, which has to be done as a separate step. When you submit a pull request, there are no reviewers by default. It means, you as an author have to add them by yourself in the corresponding tab. GitHub usually suggests who to choose as reviewers based on some previous commits. After you make your choice, the appropriate engineer will get a notification on the review request.

How many reviewers?

It depends on the size of your team or project. For small teams, there is no reason to set more than two reviewers. In most cases, one is enough. This number may increase up to 3 PR reviewers for bigger projects, with the requirement to have two approvals before the merge.

Pull request description

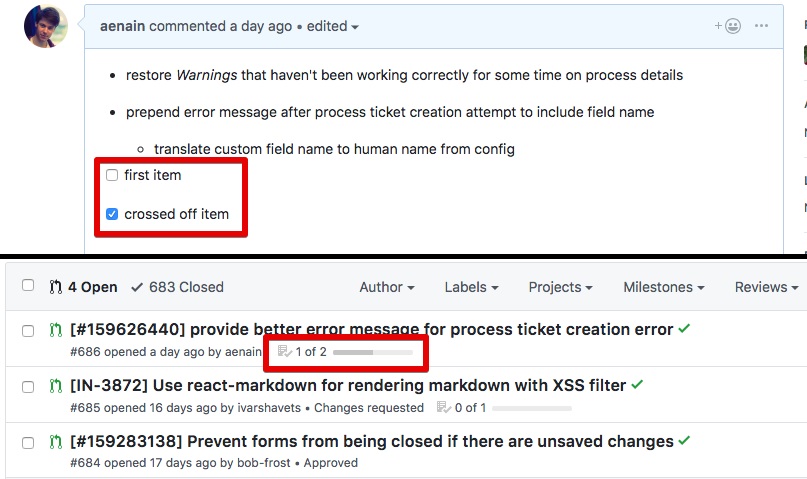

When a reviewer gets to your PR, he or she should have a general idea of what has been changed. In that case, the description should serve as a kind of lighthouse to illuminate fundamental modification and help in reviewing. You can apply the same rule to making extended commit messages. A good PR description is a shorter version of combined extended commits from the entire branch. Additionally, you can include a screenshot of the expected state.

A ToDo list or a checklist is another worthwhile element that you can embed in the description. Here is the trick to it:

- Start a list with square brackets and a space inside ‘[ ]’ for a ToDo task;

- Place square brackets with an ‘x’ inside ‘[x]’ for the crossed off (Done) task on the same line;

- Update the description and enjoy your ToDo list (besides, you will see the number of ToDo tasks below the PR title on the pull request list).

It makes sense to create checklists when you as an author review comments, to allow someone to navigate the progress.

At Railsware, we also employ post-deploy and post-merge task lists. Post-deploy tasks are essentially maintenance things that have to be done after the deployment of changes. These include content or configuration changes in third-party services. As you may have guessed, post-merge task lists cover things to do after the merge.

Shift your work experience with us – join Railsware!

Reviewing process

Let’s switch over to the reviewer’s shoes for a moment. PR review is not a trivial task, since it requires not only domain knowledge but also an understanding of the whole project’s code and company’s/team’s coding principles.

Manual approach

To make a GitHub pull request code review as efficient as possible, you should avoid reviewer’s cliches and review the code as if you were taking over the work yourself. That allows you to dive into the code and get a better understanding of it. Don’t just take a quick glimpse at the code. Start with the message, and then look over the code. After that, you can leave comments on any changed lines.

Sometimes you have to leave comments on unchanged lines, which is a bit awkward. GitHub has an issue where you cannot leave comments on code outside of changed chunks.

This approach has some challenges when it comes to big pull requests. They are hard to review because they consist of many intricate changes. Just imagine 1000+ lines of code submitted for review! Therefore, it is preferable to create small PRs. Going commit by commit may is a possibility, but it is tricky to get a good grasp of all the things that have been changed.

Besides, some of your comments regarding code/problems might not be relevant; some changes may roll back later on, etc. Still, if you have to review a big PR, commit by commit seems to be the only appropriate option.

Automatic approach

When making your pull request code review, do not forget that not everything requires a manual check. In general, the more you automate, the better. We use linters to assess code to detect stylistic errors, bugs, suspicious constructs, etc. In our toolbox, we have RuboCop for Ruby and ESLint for JavaScript.

Another non-manual solution we leverage is the continuous integration services such as CircleCI, Travis, TeamCity, Jenkins, and others to run automated tests of the code. However, things that require abstract thinking and understanding of code semantics (e.g., vocabulary cohesion) cannot be automated. These things should take most of the reviewers time, while the author should focus more on automation.

In Railsware’s GitHub practice, we employ JS checks plus ESLint and Ruby tests plus Rubocop as obligatory steps before merging PR. In addition, we use a one-of-a-kind QA-free approach to test the code. It is called TestFest and well described here.

Three outcomes of the review

Eventually, your Git pull request migrates into one of the three outcomes.

Request for changes

The first one is a request for additional changes to be made in the code. Your PR needs some follow-up revision.

Discussion

The second outcome is the most time-consuming one since it means no decision has been reached about whether to reject the PR or not. You’ll have a discussion with reviewers on whether your changes are fine or some additional modification is necessary. When it is over, you have to revisit the PR to check the new commit with changes but the same PR.

Approval

And the third outcome is approval. Reviewers are happy with the changes you’ve suggested, and you can merge them into the master branch. Additionally, you can configure checks (branch protection rules) that have to pass before merging – automated tests and linters, required pull request reviews, required signed commits or even specified people/teams allowed to push to matching branches. At Railsware, we confine ourselves to the passing of status checks only.

Updating pull requests

One of the rules we have is that the branch has to be up-to-date with the master branch. It means that we have to merge the main branch to topical branches through GitHub UI. Alternatively, the branch can be rebased and pushed with --force-with-lease. Our approach is to rebase when PR has not been reviewed yet, and to merge after that. That way is more convenient since you have less commits in the log and a flat history structure in the repository.

Once your pull request in GitHub has been reviewed, and you’ve got comments, then merging is preferable to avoid the risk of losing them. If you rebase, you have to do the push --force, which entails overwriting of all the changes. That’s why you do --force-with-lease, which means that you have to be the last person that changes the origin branch. This way you can avoid accidentally overriding someone else’s changes.

Pull request trains

Here is an interesting observation made by one of our Railswarians regarding a kind of a blocker. The idea is that you have some corresponding changes and you have to work on them one after another. So to say, you split stories more than you want to split deployments. I.e., you might have two separate stories, but you don’t want to deploy one without having all the changes done before another one. Another reason why this PR train takes place is that the previous code, which is necessary to proceed, has not been merged yet.

Solution approach

We approach this issue by switching context to deal with another task, as well as starting a new branch on top of the previous one (not from the master branch unlike Git-flow) to continue working uninterrupted. In the latter case, you should add a suffix with (number) to the PR title to make it clear. To simplify navigation, you can add ‘based on #’ to the description as well. This approach provides the possibility of easy merging to the master branch because you need to merge only the last branch. If the changes are properly merged or rebased, others will be merged as well which leads to the closure of PRs. You always have a full scope of changes and can check if everything works together.

Heroku Review Apps

With a specialized Heroku tool, you can automatically check a pull request as a standalone application. You can see how your changes will work from a UI perspective without the need to check out the branch locally. It is great when you need to introduce code changes to non-tech people for review. A huge benefit is that you don’t have to run database migrations locally. And switching between branches might cause some headaches. The problem with DB migrations is that whenever you switch between branches, you have to apply them, revert them, switch branches, and reapply them to see changes.

You can avoid this back-and-forth work using Heroku Review Apps (HRA). It creates a review app for each PR with a following update. This PR review app will be erased automatically after some inactivity period. We also use HRA to copy production database schema and run migrations on top of it. That gets us one step closer to the production environment since we can check how it really integrates when we deploy it into production.

Heroku Pipeline Promotion

This tool allows you to grab one branch and promote it from staging to production with one click in the Heroku dashboard. It is great because a product owner or a QA team can easily deploy after they perform their checks.

Continuous Delivery Concept

According to this concept, the code should always be in a deliverable state. The idea is that each commit should work and pass tests so that it can be deployed at any time. And we have this automated. In our case, we have merge-to-master followed by deployment-to-production (merge => deploy). Railswarians have this implemented on CI through a script, but it can be done as a part of Heroku configuration as well. What does it give to us? One click bears two functions – merge and then deploy. Once the action is performed, all involved engineers get a notification, which is very useful.

How long does it take from opening PR to closing it?

The hard truth is that the timeframe may vary from a few minutes to over 20 days. At Railsware, we strive to close PRs within one sprint (week). The optimum time range is 2-3 days because otherwise, you risk updating PRs one after another.

We use an approach that defines limits that are typical for kanban boards. Those are limits on how many things can be at the certain stage at any given point in time. For example, we have an unlimited ToDo list with up to 3 items in progress and up to 2 items under review. That makes the team focus on helping other team members on moving things forward. As a result, everyone helps each other with review and testing. The idea is that you cannot apply to review anything else until these two separate stories are resolved. You have to help with these reviews so the team can move forward.

In general, the pull request approval should take little time. Experience shows that the time between the request and the start of the actual review is a key bottleneck. When you actually start reviewing, you usually accomplish it fairly quickly. These two activities take up most of the time.

Wrapping Up

Railsware shares its practices so you can improve your workflow as well. Pull request review is an essential element of the coding process which demands not only engineer’s domain knowledge but also creativity, flexibility, and discipline. We do hope that you will find some hands-on application of the material described in this article. One last piece of advice – don’t deploy on Fridays, if you do not want to lose your weekend:)